FTPs, DASTCOM5 and dtypes (SOCIS 2017)

In the previous entry, I said that we had found a new database, and we would have to take a closer look to it.

Actually, what I found was a JPL public FTP, with lots of data in it (I have barely taken a glance to all the folders that contains, so have fun looking into it :P).

In that FTP, inside ssd folder (Solar System Dynamics, not Solid State Drive), there were several different files, some of them with .DB extension, some of them with .dat extension, and a README.

The README explained some of the files (a few of them are still a mystery), and I quote what it said about a file named dastcom5.zip.

dastcom5.zip

Link to a a portable/programmable version of the JPL/Horizons database of asteroids and comets ("DASTCOM5"), updated as often as hourly

Interesting, isn't it?

Well, after a week, I can now assure that this database has been a great discovery, so this week entry will address mainly about it.

DASTCOM5

As README says, DASTCOM5 is the name of a JPL-maintained database of asteroids and comets (I think D stands for Database, AST for asteroid, COM for comets, and 5 is the current version, but I'm not sure haha).

After downloading and unzipping the file that JPL provides, you can see the following folder structure:

Fortunately, dastcom5.zip provided a doc folder.

Inside this folder there was a long README (more than 1200 lines) with a lot of information, which I quote below:

DASTCOM5 is a direct-access binary database. It contains heliocentric ecliptic osculating elements for the known asteroids and comets, determined by a least-squares orbit solution fit to optical and radar astrometric measurements.

[...]

A total of 142 parameters per object are defined.

So DASTCOM5 format was binary (more difficult than JSON), but it contained 142 parameters. Not bad! Let's continue:

The DASTCOM5 distribution .zip file archive contains the following:

two binary database files (one holding asteroid data, the second holding comet data),

a plain-text index (linking all objects to their DASTCOM5 record, permitting look-up based on name, designation, SPK ID, packed MPC designation, and historical aliases),

documentation,

latest database reader source code (FORTRAN). The software has been tested using GFORTRAN (gfortran), Lahey (lf95), Intel (ifort), and SunStudio (f95) compilers in both 32 and 64-bit builds, under RedHat Linux 4/5/6.

Apparently, DASTCOM5 provided all of the necessary files for building a module poliastro.neos.dastcom5. We decided to read the two binary databases with Python instead of creating a FORTRAN wrapper, which didn't sound appealing at all.

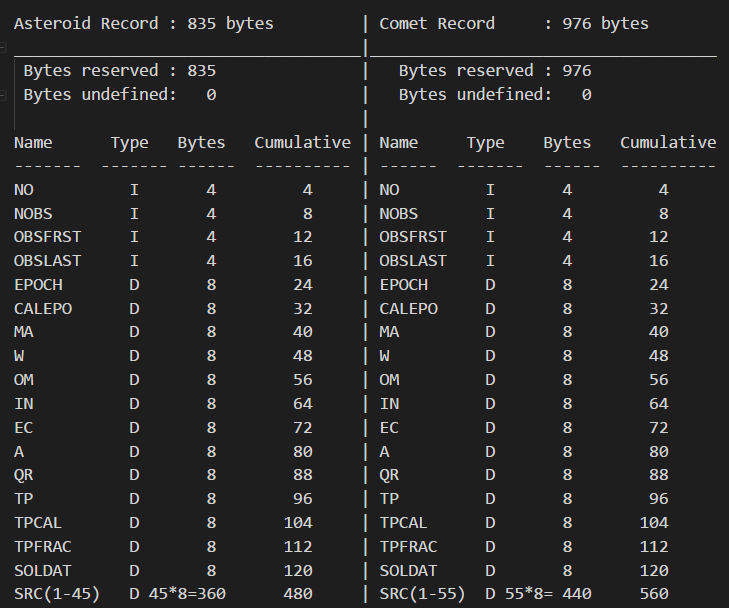

Therefore, the first task was to read a comet or asteroid binary record, and the chosen tool was numpy.fromfile(), which, as stated on its docs, needs a known data-type. Fortunately, the extensive DASTCOM5 README had a section named DASTCOM5 BYTE MAP which was really useful.

Knowing the number of bytes and type of each variable, the only difficulty was writing it for each of the 142 variables manually.

Once that was done, we were able store the full asteroid or comet database as a numpy array:

with open(AST_DB_PATH, "rb") as f:

data = np.fromfile(f, dtype=AST_DTYPE)

or obtain a single record given a physical record number using:

with open(AST_DB_PATH, "rb") as f:

f.seek(PHYSICAL_RECORD, os.SEEK_SET)

body_data = np.fromfile(f, dtype=COM_DTYPE, count=1)

However, the problem was that DASTCOM5 physical record didn't correspond to a logical record, such as 433 for Eros, or 900001 for 1P/Halley. So, the next task consisted of reading database headers in order to get information about bias between logical and physical record. The resultant function can be found, as usual, on Github.

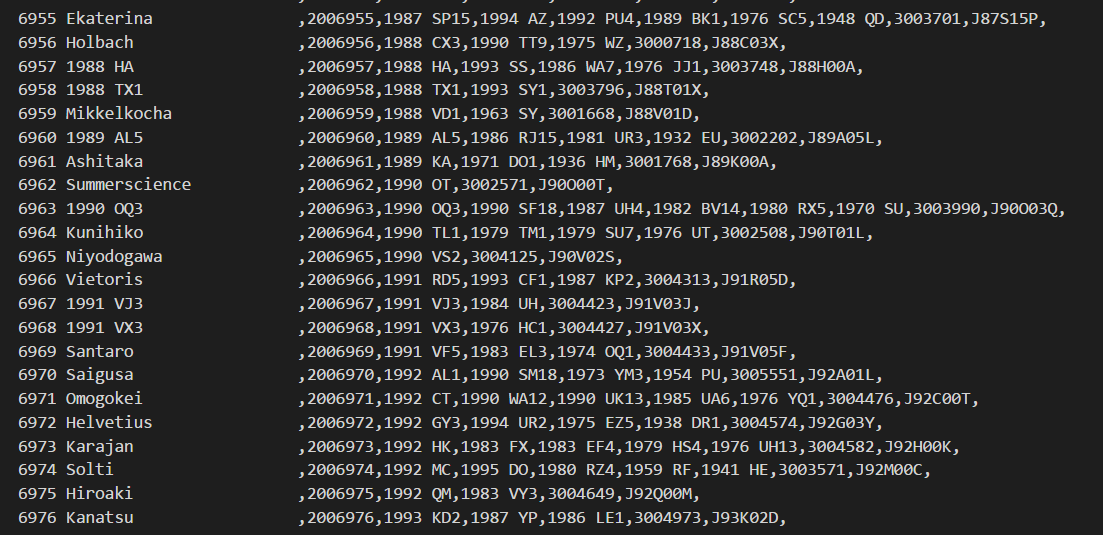

After dealing with records, it was time to start with the lookup function. As stated above, DASTCOM5 package come with a plain text index file containing names, designations, SPK-IDs, packed MPC designations, and historical aliases.

The file format was sort of CSV, but really ugly to parse, given that alternative designations, alternative SPK-IDs, etc. were all mixed without any order.

Therefore, as the file was plain text, we decided to read line by line the index, comparing with a string passed as argument. Code is on Github and anyone is welcome to improve the lookup function as well as any other part of the code :)

Downloading DASTCOM5

DASTCOM5 isn't an online API, but an online available file, which you need to download in order to use. Therefore, poliastro needed to provide a good way to download the database without having to stop Python console.

Unlike previous entry, where we used Request library in order to communicate with the internet, in this module urllib.request was chosen, since urllib.request.urlretrieve() can be called using a function as an argument, which is called after each block read. That gave us the opportunity of showing download progress, with the following code:

def _show_download_progress(transferred, block, totalsize):

trans_mb = transferred * block / (1024 * 1024)

total_mb = totalsize / (1024 * 1024)

print('%.2f MB / %.2f MB' % (trans_mb, total_mb), end='\r', flush=True)

Also, once the download function was finished, we decided to provide CLI support, adding poliastro --download-dastcom5 command.

So, from now, you can download DASTCOM5 database automatically to ~/.poliastro folder either from a Python interpreter or from CLI.

NeoWs and DASTCOM5

Both NeoWs and DASTCOM5 are currently part of poliastro.neos, and their functionalities can somehow intersect. But they are completely different in the background, with mainly two differences:

-

DASTCOM5 database has data about every asteroid and comet in the solar system, but NeoWs is only available for NEAs (Near Earth Asteroids).

-

NeoWs is an online API, but DASTCOM5 has to be downloaded in order to be used (~230 MB).

Therefore, depending on your needs, you will have to decide which one fits you better, considering that both of them can create an Orbit given a name, SPK-ID, etc.

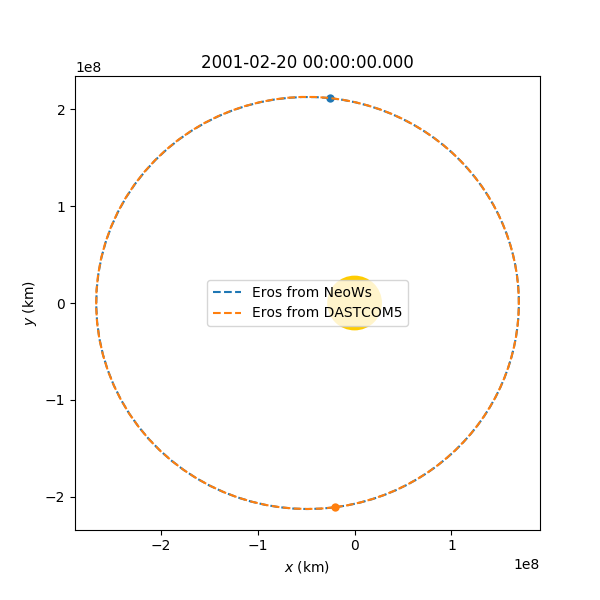

However, the resultant orbits using the two functions are exactly equal, as you can check in the following example using Eros:

In [1]: from poliastro.neos import neows

WARNING: Constant 'Earth equatorial radius' already has a definition in the None system [astropy.constants.constant]

WARNING: Constant 'Jupiter equatorial radius' already has a definition in the None system [astropy.constants.constant]

In [2]: from poliastro.neos import dastcom5

In [3]: from poliastro.plotting import OrbitPlotter

In [4]: eros_neows = neows.orbit_from_name('eros')

In [5]: eros_dastcom5 = dastcom5.orbit_from_name('eros')[0]

In [6]: frame = OrbitPlotter()

In [7]: frame.plot(eros_neows, label='Eros from NeoWs')

Out[7]:

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1e0c0d68940>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1e0b9a71438>]

In [8]: frame.plot(eros_dastcom5, label='Eros from DASTCOM5')

Out[8]:

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1e0c0e38780>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1e0c0e3a8d0>]

That was all for this week (two weeks actually, sorry for that). Now poliastro has two ways of dealing with NEOs, each one with its advantages and disadvantages, and you can try any of them. Probably, the next week entry will be about a completely different topic, not exactly related to NEOS, but I can't disclose anything right now :P See you!